Understanding Node.js

I really didn’t like Node.js or JavaScript as a programming language due to its seemingly difficult to understand programming constructs—and this made me shy away from web programming, especially front-end programming that makes heavy use of the JavaScript programming language. But with time, I started to understand the language (JavaScript) and the runtime (Nodejs). This is true for understanding anything, innit?–getting to understand the basic building blocks and fundamental ideas that stack up to become the very intricate and often intimidating-to-beginners systems. It’s a fact that if we give it time (and thorough learning), we can grok anything no matter how intricate it may seem.

I love backend engineering and my first exposure to nodejs was through the express.js framework. This is probably the way it is for most beginner programmers and the evidence is clear from many YouTube tutorials and blog posts about building web servers in Nodejs. But premature exposure to frameworks like this can make us lose sight of the fundamental idea or underlying details and principles of a programming language or runtime.

Programming Paradigms

In computer science speak, a programming paradigm is an approach or method of programming a computer based on a set of principles. Each paradigm supports a set of concepts that makes it the best for a certain kind of problem. The fact that Node.js (and JavaScript) is an event driven runtime is an often overlooked idea by beginner programmers. Nodejs uses the event driven approach of programming such that:

No function performs direct I/O, to receive data from disk, network or another process, there must be a callback. The API should be familiar to client-side JavaScript and the Unix programming interface.

—Ryan Dahl, on his initial presentation of the Node.js project.

At a very high level, nodejs event-driven approach to programming is not quite different from browser JavaScript event driven approach. For instance, I later understood that server.on() is not different from server.addLister() just like the way you add event listeners to HTMLElemnts like:

document.getElementById('btn').addEventListener(eventName, callback)

As a matter of fact, server.on() is just an alias for server.addListener(). The key idea in nodejs is, every object that will implement this functionality inherits from the EventEmitter class.

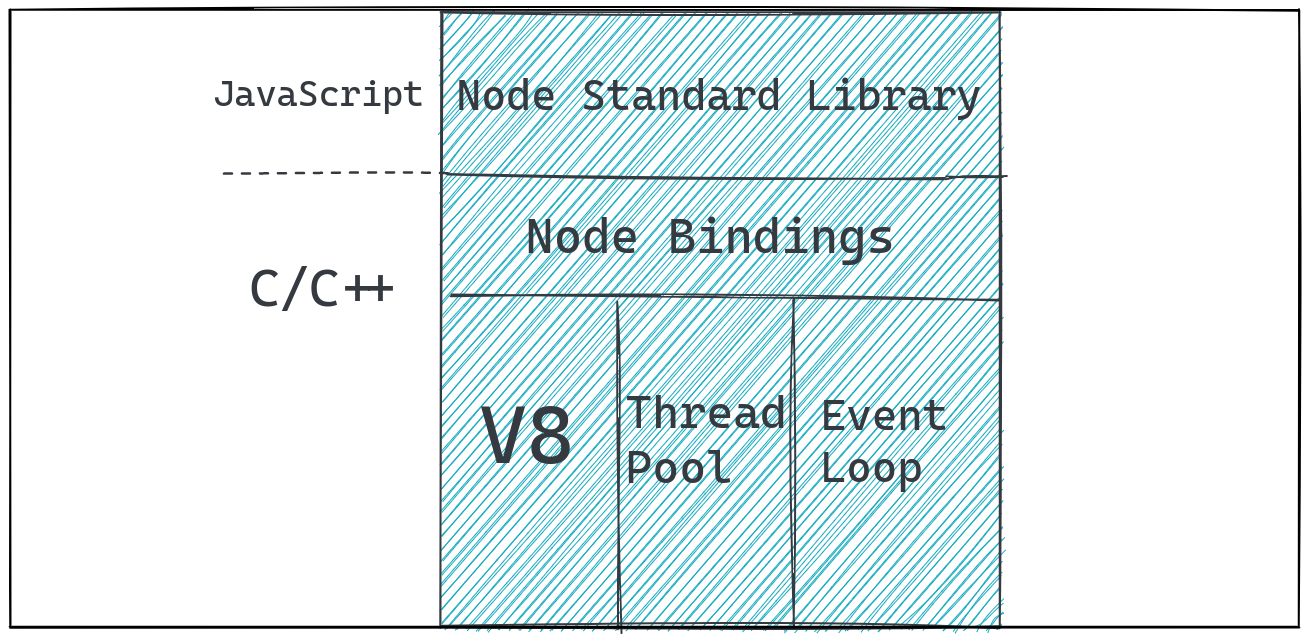

Node Architecture

Node.js is not single-threaded per se—it is the JavaScript engine responsible for executing Javascript code that is single-threaded. Saying Node.js is single-threaded is quite an oversimplification which can be misleading when using it. Node.js uses multiple threads under the hood, it just hides most of it such that the end user rarely even knows what is happening. Node.js uses more than one thread (more on that later), but only one thread—called the main thread—is exposed to the user. The author of Node.js, in his original presentation of Node.js said that programming with threads is a leaky abstraction, and that I/O needs to be done differently.

According to the Node.js docs:

When Node.js performs an I/O operation, like reading from the network, accessing a database or the filesystem, instead of blocking the thread and wasting CPU cycles waiting, Node.js will resume the operations when the response comes back. This allows Node.js to handle thousands of concurrent connections with a single server without introducing the burden of managing thread concurrency, which could be a significant source of bugs.

Event driven programming fits very well into the kind of problems that Node.js tries to solve, that is, building scalable and efficient network applications and web servers and programs that have to do with lot of blocking I/O1.The Javascript programming language provides constructs that simplifies event driven programming like closures, anonymous functions, callbacks, async/await, Promises, etc. JavaScript was chosen in implementing Node.js because it was already geared towards event-driven programming.

I also think evented programming is a very good way of programming good software that have to deal with I/O–the realworld is event driven after all! For instance, when we want to kill a running Node process, we press ctrl + c and an interrupt signal is sent which kills the running process. This is as a result of a callback function built into the process.on() method. We can even override this method such that we can no longer kill the process by pressing ctrl + c or it prints a message before exiting:

// prints hello every second (at least)

setInterval(() => {

console.log("hello");

}, 1000);

// the on method adds an event listener to

// the named event

process.on("SIGINT", () => {

console.log("I'm leaving");

process.exit(0);

});

// process.addListener("SIGINT", ()=>{

// // this is an alias for process.on()

// })

Running the above program wil print “I’m leaving” before exiting. Should we remove the process.exit(0) code, the program will no long stop on ctrl+c. We will have to kill it with the task manager of the operating system.

Events and EventEmitters.

According to the Nodejs docs:

Much of the Node.js core API is built around an idiomatic asynchronous event-driven architecture in which certain kinds of objects (called “emitters”) emit named events that cause Function objects (“listeners”) to be called.

For instance: a net.Server object emits an event each time a peer connects to it; a fs.ReadStream emits an event when the file is opened; a stream emits an event whenever data is available to be read.

All objects that emit events are instances of the EventEmitter class. These objects expose an eventEmitter.on() function that allows one or more functions to be attached to named events emitted by the object. Typically, event names are camel-cased strings but any valid JavaScript property key can be used.

The evenEmitter.on() method is as alias for eventEmitter.addListener() method. This can be found here in the Node.js source. The eventEmitter.addListener() looks more intuitive for someone that comes from frontend programmer where they attach events to an HTMLElement using the elem.addEventListener() method that the browser API exposes.

Node Event Loop

It as a C program and is part of libuv. It is a design pattern that ochestrates or co-ordinates the execution of synchronous and asynchronous code in Node.js in six different queues. All JavaScript, V8, and the event loop run in one thread, called the main thread. A common misconception is to think that the event loop runs in a separate thread to the user code or the event loop handles every asynchronous operation in the thread pool.

Whenever an async task completes in libuv, at what point does Nodejs decide to run the associated callback function on the call stack? Callback functions are executed only when the callstack is empty. The normal flow of execution will not be interrupted to run a callback function.

What about async methods like setTimeout and setInterval which also delay the execution of a callback function? setTimeout and setInterval callbacks are given priority first.If two async tasks such as setTimeout and readFile complete at the same time, how does Node decide which callback function to run first on the call stack? Timer callbacks are executed before I/O callbacks even if both are ready at the exact same time.

Execution of different callbacks is in phases:

Phases.

Microtask Queues.

Microtask queues are executed in between each queue and also in between each callback execution in the timer and check queues.

- nextTick queue.

process.nextTick(() => { console.log("this is process.nextTick()"); });process.nextTick()should be used with caution as it can cause the rest of the event loop to starve due to its high priority. If you endlessly or carelessly callprocess.nextTick(), the control will never make it past the microtask queue. - Promise queue. Any API or function that returns a promise.

Promise.resolve().then(() => {

console.log("this is a promise");

});

Timer queues.

They are executed in FIFO order…although the timer queue is a min heap data structure.

- setTimeout queue.

setTimeout(() => { console.log("this is a timer callback"); }); - setInterval queue.

I/O queue.

Most of the async methods for perform i/o operations from the built-in modules queue the callback

function in the I/O queue. e.g fs.readFile(). I/O queue callbacks are executed after timer queue callbacks. I/O polling events are polled and callback functions are added to the I/O queue only after the I/O is complete.

Check Queue.

To queue a function into the check queue, we can use the setImmediate() function.

setImmediate(() => {

console.log("setImmediate function for check queue");

});

check queue callbacks are executed after microtask queues callbacks, timer queue callbacks and I/O queue callbacks are executed.

Close queue.

Close queue callbacks are executed after all other queues callbacks in a given iteration of the event loop are executed. Callbacks are added to the close queue by adding event listeners to close event.

Execution Order.

User written sychronous JavaScript code takes priority over async code that the runtime would like to execute. The other of execution for the different phases is as follows:

- Any callbacks in the micro task queues are executed. First, tasks in the

nextTick()queue and only then tasks in the promise queue. - All callbacks within the timer queue are executed.

- Any callbacks in the micro task queues if present are executed. Again, first tasks in the

nextTick()queue and only then tasks in the promise queue. - All callbacks within the I/O queue are executed.

- Any callbacks in the micro task queues if present are executed. Again, first tasks in the

nextTick()queue and only then tasks in the promise queue. - All callbacks in the check queue (

setImmediate) are executed. - Any callbacks in the micro task queues if present are executed. Again, first tasks in the

nextTick()queue and only then tasks in the promise queue. - All callbacks in the close queue are executed.

- Any callbacks in the micro task queues if present are executed. Again, first tasks in the

nextTick()queue and only then tasks in the promise queue.

If there are more callbacks to be processed, the event loop is kept alive for one more run and the same steps are repeated. On the otherhand, if all callbacks are executed and there is no more code to process, the event loop exits.

-

Blocking I/O has to do with data fetch outside RAM from disk, network or other processes and takes so much CPU cycles, unlike non-blocking I/O that have to do with data fetch from CPU caches or at most RAM and takes fewer CPU cycles.